CyberRoadmap — Understanding Linux Special Permissions

This guide explores special permissions in Linux - SUID, SGID, and the sticky bit. Discover how these advanced tools can enhance security and facilitate collaboration on your system.

From the same series

In the previous article, we covered the fundamental rwx permissions that everyone uses. But the Linux permission system has a few more tricks up its sleeve to handle special cases. These are the special permissions: SUID, SGID, and the sticky bit.

The SUID Bit: Running as the Owner

The SUID (Set User ID) bit is a fascinating permission. When it’s set on an executable file, it tells the system to run that program with the permissions of the file’s owner, not the user who’s running it.

You’ll often see the s in place of the x in the owner’s permission field when you run ls -l. For example, rwsr-xr-x.

A perfect example is the passwd command. When you run passwd, it needs to modify the /etc/shadow file, which only the root user can write to. The passwd command is owned by root and has the SUID bit set. This allows a normal user to change their password without having to be root.

Practice

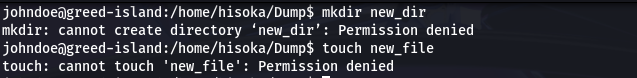

Let’s consider two user hisoka and johndoe. johndoe can’t create file and directory in the directory /home/hisoka/Dump cause it’s owned by hisoka.

1

drwxrwxr-x 2 hisoka hisoka 4096 Sep 1 02:04 Dump

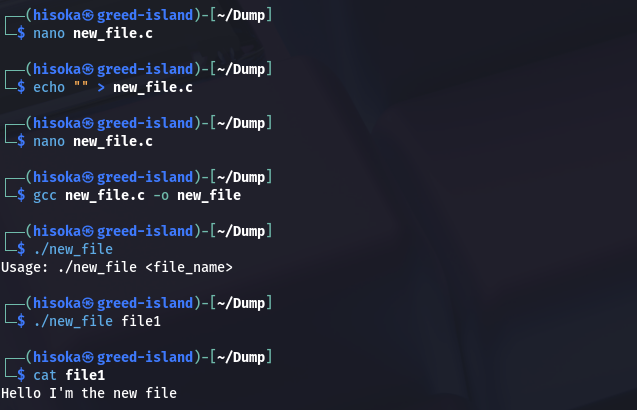

Let’s create a script that allow to create a new file containing Hello I'm the new file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s <file_name>\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

// Open the file for writing, create if it doesn't exist

int fd = open(argv[1], O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC, 0644);

if (fd == -1) {

perror("open");

return 1;

}

// Write the content

const char *content = "Hello I'm the new file\n";

ssize_t bytes_written = write(fd, content, strlen(content));

if (bytes_written == -1) {

perror("write");

close(fd);

return 1;

}

close(fd);

return 0;

}

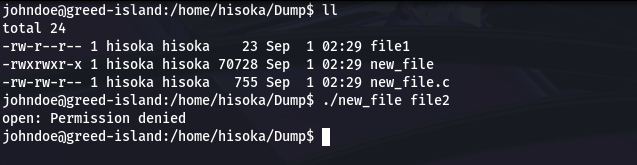

But when johndoe tries to use this command…

It’s important to know that johndoe has the permission to execute the script (-rwxrwxr-x new_file.sh) but the line 5 of the script doesn’t match with permission set of the directory Dump.

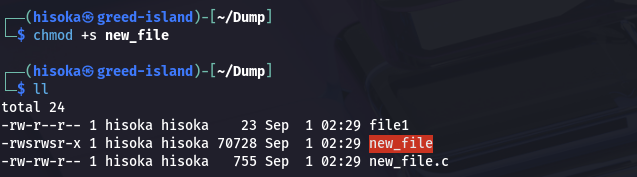

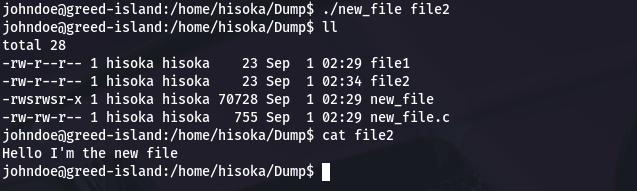

Let’s try to set the SUID bit and see how it’s going.

Now johndoe can successfully create a new file with thanks to SUID bit.

In security, it may be problematic because if the script executes critical operations on the system, it can lead to information disclosure, data thief, or privilege escalation.

The SGID Bit: Sharing Group Privileges

The SGID (Set Group ID) bit works similarly to SUID, but for groups. When it’s set on an executable file, the program runs with the permissions of the file’s group.

The most common use of SGID, however, is on directories. When the SGID bit is set on a directory, any new file or subdirectory created within it will automatically inherit the group ownership of the parent directory.

This is extremely useful for collaborative projects. Imagine a directory shared by the developers group with the SGID bit set. If a user named alice creates a new file, it will automatically belong to the developers group. This means every member of that group can immediately access and edit it, without anyone needing to manually change permissions.

You’ll see the SGID bit as an s in the group’s permission field.

The Sticky Bit: Protecting Shared Files

The sticky bit is a special permission that is almost always used on shared, world-writable directories. Its purpose is simple: it prevents users from deleting or renaming files they don’t own.

You’ll see the sticky bit as a t in the “others” permission field, like in the /tmp directory (drwxrwxrwt).

Without the sticky bit, any user could delete any file in /tmp, which would cause chaos. The sticky bit ensures that a user can only delete their own files, even though everyone has write access to the directory.

These special permissions are powerful tools that help maintain security and streamline collaboration on a Linux system. They’re a core part of what makes Linux so flexible and robust.